Supporting communities of practice

These notes are part of a series for the book.

Outline

- Defining communities of practice

- Feature-based definition of community of practice

- Defining communities of practice as a process

- Communities of practice versus other knowledge communities

- Technology and communities of practice

- Summary

Notes

History of the idea

The author starts with a history of the term “community of practice”. It’s commonly attributed to Lave and Wenger but there are earlier works and later developments as scholars moved from describing communities of practice to defining possible ways of using and nurturing them for organizational learning:

- 1987: Edward Constant (in ‘The social locus of technological practice: Community, system, or organization?’)

- 1987: Jean Lave (in Cognition in practice)

- 1990: Julian Orr (in ‘Sharing knowledge, celebrating identity: Community memory in a service culture’)

- 1991: Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger (in Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation)

- 1991: John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid (in ‘Organizational learning and communities-of-practice: Toward a unified view of working, learning, and innovation’)

- 2002: Etienne Wenger, Richard McDermott, and William Snyder (in Cultivating communities of practice: A guide to managing knowledge)

Features

Some definitions of a community of practice focus on its features:

- It’s a community that shares practices.

- Knowledge is tacit, and made explicit through the social interaction people have while solving problems.

- Knowledge is embedded in practices, especially the practices of the organization, the socio-technical system, and more generally the culture

- Some knowledge is “sticky”: stuck within a group of people even though there are pressure to share, or stuck within a group of people because it is difficult to spread around. Other knowledge is “leaky”: it spreads even though there is pressure to keep it within a group of people. Knowledge can be sticky and leaky at the same time.

- Knowledge is not in the head (a cognitive construct), nor is it conditioned by the environment (behavioral).

- We must put learners in realistic contexts so they can “do” the knowledge.

Processes

Some definitions of a community of practice focus on its processes:

- Learners enter communities and gradually adopt the community’s practices.

- We must provide access to experts, help learners want to be members, provide an already-existing community with a shared history and identity, and allow for “lurking” and peripheral participation.

Difference between this and other knowledge communities

Within knowledge-building communities:

- The goal is explicitly about learning (that is, learning is not incidental)

- The community is designed and a specific agenda is set by its members or from outside the group

Within communities of practice:

- The goal isn’t learning, even though learning occurs

- The community comes about organically

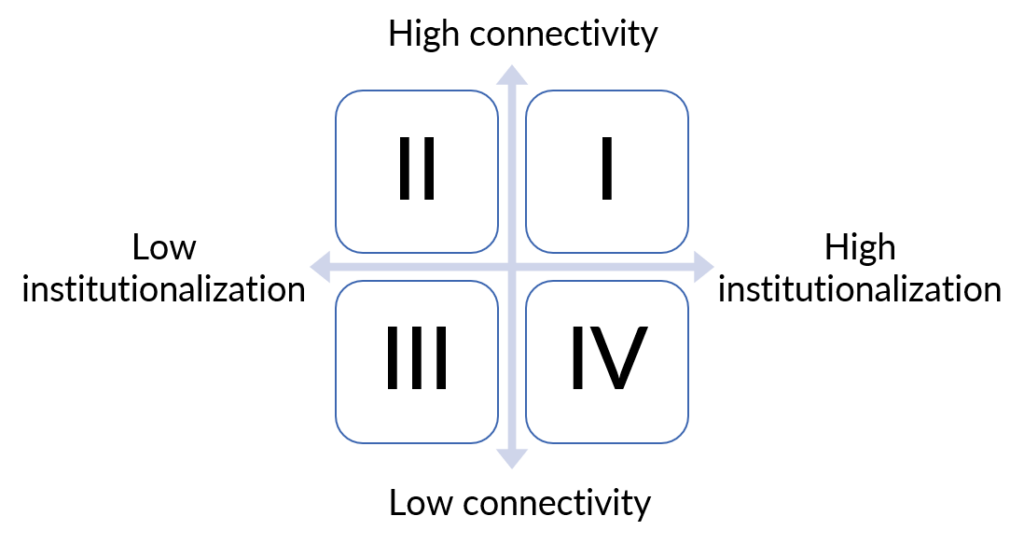

Andriessen (2005) further defined different communities by plotting them on two dimensions: how connected the members were as a group, and how institutional or formalized the group was. This helps us explore where communities of practice fit within the larger context of communities. If placed in quadrants, his taxonomy looks like this:

- Quadrant I: These are strategic communities, which may include any communities of practice that come together for project-based teams.

- Quadrant II: These are informal communities, which includes communities of practice.

- Quadrant II-III: Groups with some connectivity but low institutionalization are informal networks, and this includes communities of interest and professional networks.

- Quadrant III: These are interest groups. They have shared interests but no cohesion.

- Quadrant IV: These are rarely-studied communities such as those made up of people who complete surveys to help pollsters find consensus among groups without supporting any inter-personal contact.

See also: I think there’s an interesting overlap between Andriessen’s taxonomy and Dron and Anderson’s (2014) groups, nets, sets, and collectives.

Supporting communities of practice with information technology

Technology can support communities of practice in three areas:

- Content: Storing and searching in multiple formats, processing digitally.

- Process: Scaffolding a task, activity, or sequence of actions (for example, document routing, or steps in an inquiry for learning)

- Context: Supporting the changing contexts of users

Fostering community with information technology

Technology can foster community in four strategic areas (this is the C4P model):

- Content: Providing a shared repository of information resources.The community uses these resources, but the knowledge is in the community itself.

- Conversation: Providing discussion tools.

- Connections: Linking people with similar practices by supporting connectivity and connections. This may include helping people find others with similar practices, including novices and peripheral participants who may not know more central members of the community. Members may find each other with this connection and then later deepen their relationship with the community.

- Information context: Providing context for stored information or information available to members — how did it get here, how did it begin, what else might a person like or want?

See also

An analysis of how the idea of communities of practice have evolved over time: Cox, A. (2007) ‘Reproducing knowledge: Xerox and the story of knowledge management’, Knowledge Management Research and Practice, 5(1), 3-12.