The workplace curriculum

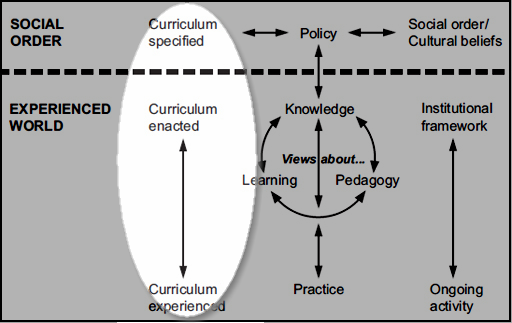

These notes are part of a series for the book. This article looks at how a workplace curriculum is shaped and organized. The framework used in The Open University’s E846 module discusses curricula in these terms:

- Specified curriculum (Billet calls this intended curriculum and, see below, Lave calls this the learning curriculum): What is intended to happen

- This ‘takes as its starting point an anthropological conception of curriculum as participation in social practice, Lave’s (1990) ‘learning curriculum’ (Billet, 2012, p. 62).

- See also: Billet also discusses Lave’s learning curriculum in Billett, S. (2004) ‘Workplace participatory practices: Conceptualising workplaces as learning environments’.

- Enacted curriculum: What actually happens when the curriculum is enacted

- Experienced curriculum: What the learners experience and learn as a result, when the curriculum is enacted

The Open University, E846 framework for analyzing practice, with curricula highlighted

Outline

- Workplace curriculum as intentions

- The enacted workplace curriculum

- The workplace curriculum as experienced by workers

- A curriculum for the workplace and beyond

Notes

The workplace’s intended (specified) curriculum

There are several things to look at in the workplace intended (aka specified, or learning) curriculum:

- It is an ideal, but whose ideal?

- Focus on how learners learn tasks and also focus on developing their potential through work experiences: ‘A goal for vocational curriculum is to assist individuals to identify and realize their full vocational potential’ (Billett, 2012, p. 63).

A curriculum is not a series of classes to take and pass. Instead it is a sequence of tasks to learn and practice, to secure continuity of the work practice. As such, the workplace curriculum addresses two considerations:

- Developing the skills that the company needs to continue and prosper in its business

- Developing those skills in ways that do not put the company’s survival in jeopardy

Billett gives hairdressers as an example. They move through an apprenticeship in which they learn by directly interacting with other hairdressers and customers, and also indirectly by observing and listening to the activities around them. They progress through a series of incrementally more challenging tasks in their development. Billett also notes that the specific apprenticeship, or learning, path may be different across companies in the same industry — for example, one hairdressing shop may have a different ordering of the tasks to master than another.

The intended curriculum should make explicit the things the worker should know, including work practices that are often hidden or hard to know. He also notes that ‘more experienced workers may not always be the best judges of what comprises difficult workplace tasks for learners’ (Billett, 2012, p. 65).

The workplace’s enacted curriculum

What is specified is not what’s enacted. There are several reasons for this:

- Things like teacher experience, values, preferences, competence, interpretation, and selection. But, this isn’t necessarily a bad thing — for example, it means that teachers provide stories and examples, which are important to learners.

- Availability — which ‘opportunities, interactions, resources, and infrastructure’ (Billett, 2012, p. 66) are available to students to enable and support the goals of the specified curriculum. Billett calls this the ‘available curriculum’. Access and availability can be increased or decreased due to (Billett, 2012, pp. 66-67):

- The business needs and general profitability (more when production is high; less when it is low)

- Legal requirements (more when required by law)

- Need for workers (more to attract and keep workers, less when this is not a concern)

- Need for control (more when managers are less fearful, less when managers want to restrict workers due to fear)

- Need for mobility (more when the company has many upper positions to fill, less when they have fewer positions open)

- Full-time versus contract labor (more when workers are employees, less when they are contractors

- Workers’ actions and beliefs. For example:

- Experts may not help novices if they fear that it will jeopardise their job security

- Workers will be more or less willing to help others who are or are not in the same cliques, or share the same gender, race, or language

- Societal demands. For example:

- Learning experiences for nurses differ than those for doctors, unless there is a supply/demand difference that requires nurses to learn some of the skills usually taught only to doctors.

The workplace’s experienced curriculum

The curriculum that is specified, and the curriculum that is enacted, is not the same as the curriculum that is experienced by the workers. Reasons (Billett, 2012, pp. 68-70):

- During learning, people bring their own motivations and desires to the learning activities, such as the desire to be finished first, or to please the teacher, or to be recognised as being smart. These motivations affect how they engage with the curriculum.

- Learners focus on their goals and interests, and their identities. In turn, when the learners exercise agency, their decisions can affect the company.

- Learners must believe that there is something in the learning activities for them, and that they can benefit from it in some way.

See also

Wenger’s discussion about paradigmatic trajectories: Wenger, E. (1998) ‘Ch. 6, Identity in practice’, in Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity.

Limits placed on people when they are using their agency to define identity and establish a trajectory: Hall, K. (2008) ‘Leaving Middle Childhood and Moving into Teenhood: Small Stories Revealing Identity and Agency’.