Learning architectures

These notes are part of a series for the book.

Outline

- Dimensions

- Participation and reification

- The designed and the emergent

- The local and the global

- Identification and negotiability

- A design space

- Components

- Facilities of engagement

- Facilities of imagination

- Facilities of alignment

- A design framework

Notes

Learning

‘Learning cannot be designed’ (Wenger, 1998, p. 225). Learning can be done within a community of practice (COP), or within a different kind of community, or outside of any community at all. Sometimes it is best to learn in groups, and sometimes it is best to learn alone. COPs are not new — they’ve always existed — and they aren’t ‘a new kind of organizational unit or pedagogical device to be implemented’ (Wenger, 1998, p. 228). You can’t form COPs, but you can nurture them.

Four dimensions of designing for learning

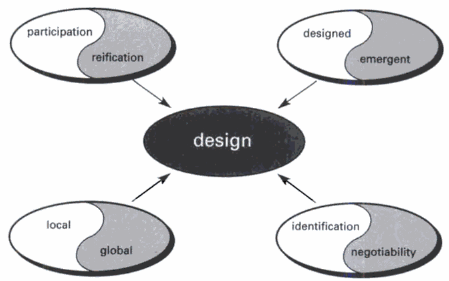

The four dimensions are actually four dualities, which should not be seen as opposite ends of spectrums but instead as tensions within their interactions:

Four dimensions of design for learning (Wenger, 1998, p. 232)

Participation and reification

Since you must have both participation and reification, the design decision is how to divide the design across the two.

| Characteristic | Participation | Reification |

|---|---|---|

| They are one of the four dimensions for learning design | Make sure the right people are available during learning. | Provide some of the right artifacts (such as curricula and procedures). |

The designed and the emergent

Practice is always emergent, always changing in response to new events. Identity is also emergent, coming out of the creation of trajectories. This leaves the question of how to design for what is ultimately emergent. ‘[P]ractice cannot be the result of design, but instead constitutes a response to design’ (Wenger, 1998, p. 233). If a design is too rigid or prescriptive, it might inhibit that which it attempts to encourage. Design must include space for the emergent nature of practice and identity formation.

The local and the global

COPs ultimately choose the learning they will undertake, and how to bring newcomers into their COP, so it is critical that they be involved in any design that is to benefit them. Successful design cannot be done wholly by training departments, management, and so on. However, a COP can’t fully design their own learning, because they need access to other practices. To meet this duality, a design should be seen as ‘a boundary object that functions as a communication artifact around which communities of practice can negotiate their contribution, their position, and their alignment’ (Wenger, 1998, p. 235).

Identification and negotiability

Identification and negotiability are the processes for forming identity. Design, then, requires the power to shape communities and economies of meaning.

Modes of belonging

To form learning communities, the learning design must be built on components from the modes of belonging.

| Characteristic | Engagement | Imagination | Alignment |

|---|---|---|---|

| As parts of the infrastructure of learning design | Mutuality: Interactional facilities: Places, technologies, time, and budget that support interaction Joint tasks: For participants to do, with support as needed Peripherality: Ways of negotiating the periphery, such as boundary encounters, peripheral participation, entry points Competence: Initiative and knowledgeability: Activities for knowledgeable engagement, opportunities to apply skills, and problems that increase energy, creativity, and inventiveness Accountability: Opportunities to evaluate and make decisions, negotiation of joint enterprises Tools: Artifacts to support competence, tools to understand terms and concepts Continuity: Reificative memory: Repositories of information and documentation Participative memory: Generational encounters, apprenticeships, example trajectories, and storytelling | Orientation: Location in space: Reification of constellations, maps and visualization tools Location in time: Trajectories, lore, museums Location in meaning: Explanations stories, examples Location in power: Org charts and transparent explanations of processes Reflection: Models of patterns, comparisons with other practices, retreats, conversations, and other breaks to support reflection Exploration: Opportunities and tools for exploring, envisioning possibilities and trajectories, simulations, creating alternate scenarios, building prototypes | Convergence: Common focus or interest, direction and vision, values and principles Coordination: Standards and methods: Processes and procedures, schedules and deadlines, division of labor Communication: Information transmission, renegotiation Boundary facilities: Boundary practices, brokers, boundary objects, support for multimembership Feedback facilities: Data collection and measurement Arbitration: Policies, contracts, conflict resolution, enforcement, distribution of authority |