Community responses to accessibility

These notes are part of a series for the book. In this chapter, Seale uses Wenger’s work on communities of practice to shape her discussion of how stakeholders respond to accessibility. In her concluding remarks she notes that a weakness to this approach is that it does not investigate ‘conflicts and contradictions and the influence this may have on the development of practice’ (Seale, 2014, p. 282).

Outline

- Introduction

- Communities of practice as a potential tool for analysis

- A practice that gives structure and meaning to what a community does

- Practice that is a source of coherence

- Practice that has boundaries and peripheries that may link with other communities

- Boundary objects

- Brokers

- Boundary practices and constellations

- Applicability of communities of practice to e-learning and accessibility

- One community of practice or a constellation of practices?

- In pursuit of an enterprise

- Developing a coherent community

- Creating links between communities

- Boundary objects

- Brokers

- Boundary practices

- Conclusion

Notes

Note: Seale refers to “staff developers” as a stakeholder that I think is closely aligned with the role of an instructional designer. Thus, my notes here refer to “instructional designers” even though that is not a term the author uses.

Communities of practice (COPs)

There are several communities involved in accessible elearning:

- Students, elearning users, disabled people, and web communities make up some of the communities interested in accessible elearning for learners.

- Web developers and designers, library workers, advocacy groups, and education providers are interested in providing accessible elearning.

Communities are people who come together for a specific purpose. Practice is the community’s focus. An outcome of a practice is meaning.

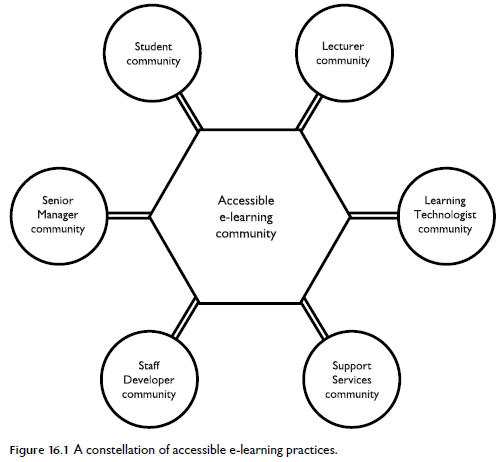

Seale’s book has discussed elearning in terms of the six stakeholders she identified in the first chapter. The six stakeholders can be seen as six COPs.

Negotiation of meaning

To negotiate meaning, a community engages in participation and reification. Participation is the interaction between members of the COP. Reification is the process of creating artifacts as a result of that participation.

For example, a team of instructional designers may have a meeting to discuss accessibility techniques (participation), and then write down the decisions made in that meeting (reification).

Mutual engagement, joint enterprise, and shared repertoire

A practice has these three dimensions. Mutual engagement are the relationships and norms in the COP. A joint enterprise is the reason they have come together as a COP. A shared repertoire can include tools, stories, and common ways of handling various circumstances.

- See also: Wenger’s three dimensions of practice

For example, a team of instructional designers) have a joint enterprise of creating accessible learning resources. Their shared repertoire of resources includes artifacts such as the accessibility guidelines they’ve adopted for their team.

Seale contends that the COPs involved in accessible elearning have shared tools such as policies, guidelines, and standards, but lack a strong shared repertoire of actions, ways of doing things, stories, and concepts. I thought she had important advice embedded in her definition of each of these:

- ‘actions: not everyone within this community is using these tools and procedures;

- ways of doing things: not everyone within this community understands what the ‘way of doing things’ is (e.g. how to interpret and implement these tools and procedures meaningfully) and there is disagreement over whether there should be ‘one best way’ or a range of ‘acceptable ways’ that can be adapted to suit different purposes and contexts;

- stories: the literature within this community is predominantly recording arguments about why tools and procedures should be used and is failing to record detailed stories (case studies, rich descriptions) of how these tools and procedures are being used and adapted in local contexts;

- concepts: in order for a coherent practice to emerge and develop, the community needs to develop its conceptualisations of what best practice is and what factors influence that practice.’

(Seale, 2014, p. 278)

Boundaries and constellations

Every COP has boundaries — people are members of the community, or not. COPs can be loosely grouped together into constellations.

- See also: Wenger’s chapter about boundaries, and about modes of belonging.

The six stakeholders/COPs that Seale identifies function as a constellation for the work around accessible elearning:

(Seale, 2014, p. 274)

- Seale references two chapters in this book for a closer look at work taken up at the constellation level:

- Forming partnerships to work together, in Ch. 9

- Becoming jointly responsible, in Ch. 10

Boundary objects and brokers

Each community makes and uses artifacts as part of reification. Sometimes those artifacts are used by people in another community. When this happens, that artifact is a boundary object. Somewhat similarly, people all belong to multiple communities, and this is called multi-membership. When multi-membership requires a person to translate, coordinate, and align between two or more communities, they are being a broker.

As an example of boundary objects, the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) are reifications. They are the result of the W3C community participating in a joint enterprise of defining accessibility standards for the Web. Their decisions were reified — written down — as the published guidelines. The six COPs that Seale identifies and that is shown in the image above have used the WCAG within their own participation, and they have reified their results as standards and guidelines meant for their community. The same is true for accessibility laws: these are reifications that are used by other COPs in their own joint enterprises, resulting in further reifications.

- Seale references back to several other chapters in this book for a closer look at laws, policies, and procedures:

- Laws, guidelines, and standards, in Ch. 4

- Procedures, processes, and strategies, in Ch. 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10

- Validation and evaluation tools, in Ch. 7

- Procurement and audit tools, in Ch. 10

Seale provides a list of published research into the reifications, or artifacts created by these COPs in response to WCAG and legislation (Seale, 2014, p. 275), and it is notably a thin list for staff developers (instructional designers) and senior managers. That doesn’t mean that instructional designers and senior managers are not doing this; it means that there are few academic articles published about their doing it.

At the same time, Seale identifies these same two groups as ones that may be the stakeholders best positioned to be brokers in the constellation of COPs interested in accessible elearning.

The balance of participation and reification

Wenger warns that participation and reification are a duality and must somewhat be in balance. If there is too much reification, then you can’t get meaning from the participation. If there is too little reification, then people will learn the shortcut without learning or remembering the concepts behind it.

This chapter of Seale’s book was only included in the first edition, which she wrote in 2005-2006. At that time, she concluded that many of the COPs were more focused on reification at a their community level than participation when in came to accessible elearning matters.

- Seale references back to several other chapters in this book for a closer look at the reification COPs are doing at their community level:

- Guidelines, in Ch. 4

- Procedures for evaluating learning resources, in Ch. 7

- Procedures for evaluating services, in Ch. 10

‘However the more recent attempts to re-appropriate reification by re-framing and adapting tools and procedures would suggest that the balance between reification and participation may soon be restored through the interactive negotiation and sharing of experiences about how best to re-frame and adapt the tools and procedures which the community has inherited’ (Seale, 2014, p. 277).