Identity in practice

These notes are part of a series for the book.

Outline

- Negotiated experience: participation and reification

- Community membership

- Trajectories

- Learning as identity

- Paradigmatic trajectories

- Generational encounters

- Nexus of multimembership

- Identity as multimembership

- Identity as reconciliation

- Local-global interplay

Notes

Overlaying Wenger’s ideas with a different framework

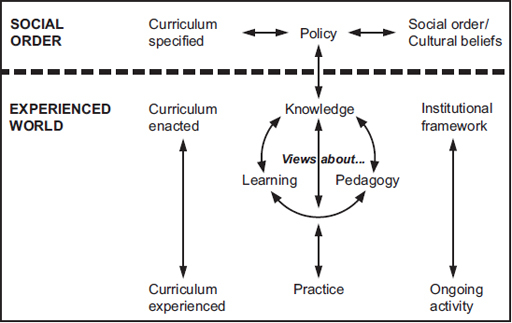

One can combine Wenger’s ideas in this chapter with the framework used in The Open University’s E846 module :

The Open University, E846 framework for analyzing practice

- Specified curriculum: This is the same as Wenger’s learning trajectories.

- Enacted and experienced curriculum: On these levels of curriculum, pay attention to the negotiation of meaning and the duality of participation and reification, and how this supports mutuality.

Identity and practice

‘Learning constitutes trajectories of participation…. [and] means dealing with boundaries’ (from the 13 principles defining learning, Wenger, 1998, p. 227).

Identity and practice are connected:

- Practice involves negotiation of ways of being; a community of practice (COP) also involves negotiating identities.

- Similar to practice, identity is:

- Negotiated experience, defined by our participation and the ways other reify our selves

- Community membership and non-membership (both the familiar and the unfamiliar)

- Learning trajectory from where we were and where we are going

- Nexus or reconciliation of our multiple memberships into one identity

- Belonging, which is defined globally but which we experience locally

(Wenger, 1998, p. 149)

Identity is a negotiated experience

Identity in practice is not the same as self-image, and identity is not what others say about us (although those are part of our identity). Instead, identity in practice is defined socially as a lived experience in COPs.

Identity is our community membership, and non-memberships

| Characteristic | Mutual engagement | Joint enterprise | Shared repertoire |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competence | We learn how to interact with others and work together. | Our investment in the community shapes our understanding of the conditions within and faced by the community. | We know the COP's shared history through its 'artifacts, actions, and language' (Wenger, 1998, p. 153). |

| Identity | We are 'part of a whole through mutual engagement' (Wenger, 1998, p. 152). | Our understanding shapes our perspective, which leads members to make similar decisions, come up with similar interpretations, and have similar values. | We have personal experiences and memories of negotiation with the COP's repertoire. |

‘In practice, we know who we are by what is familiar, understandable, usable, negotiable; we know who we are not by what is foreign, opaque, unwieldy, unproductive’ (Wenger, 1998, p. 153).

Identity is our learning trajectory from where we were to where we are going

Our identity is not static. We constantly renegotiate it through a process or participation and reification within COPs. This process forms trajectories of movement. There are 5 types of trajectories within COPs:

- Peripheral: Staying in the periphery of a community

- Inbound: Newcomers may be in the periphery in the beginning, but are working toward future participation

- Insider: Even when you are fully a member of a COP, you are still renegotiating your identity as the practice evolves

- Boundary: Crossing the boundaries between COPs

- Outbound: Leaving a COP

Our trajectory helps us decide what is important or not to our continued process of identity. Tasks take on different meanings and levels of importance based on our trajectory. For example, a person holding a job as a means of working their way through school will have a different perspective on participation and identity at work than a person for whom the job is part of their chosen career.

There are also ‘paradigmatic’ trajectories. These are not formal milestones like career ladders. Instead, they are the examples and stories of community members. Old-timers in COPs are examples of its possible trajectories. Newcomers contribute new models. Both old and new are shared as part of participation and reification. ‘Exposure to this field of paradigmatic trajectories is likely to be the most influential factor shaping the learning of newcomers’ (Wenger, 1998, p. 156).

- See also: The importance of having access to trajectories, Billett, S. (2006) ‘Constituting the Workplace Curriculum’.

There’s also an interplay between the newcomers and old-timers:

- Newcomers want continuity: Newcomers try to relate to the community’s past and history to vicariously make it part of their own identity, so they want continuity.

- Old-timers want discontinuity: Old-timers are more confident and invested in the community’s future, so they are more open to discontinuity and see newcomers as bringing new potential to the community because they are not as tied to the past.

The tension between old and new, continuity and discontinuity, is important for the COP’s growth and evolution.

Identity is the nexus or reconciliation of our multiple memberships into one identity

We all belong to multiple communities, with varying levels of centrality to our identity. Within each, we are on a trajectory. Each community has its own ways of being, negotiating, etc., and in that way they are distinct communities. However, within us each interact and influence each other as they are all aspects of our selves. Bringing the strands of trajectories together requires reconciliation. This is especially true when the different practices require different ways of responding on the 3 dimensions (engagement, being accountable to the enterprise, or negotiating the repertoire).

This reconciliation is very difficult when moving from one COP to another. ‘For instance, when a child moves from a family to a classroom, when an immigrant moves from one culture to another, or when an employee moves from the ranks to a management position, learning involves more than appropriating new pieces of information. Learners must often deal with conflicting forms of individuality and competence as defined in different communities’ (Wenger, 1998, p. 160).

This reconciliation is ongoing and is at the very center of identity. The work in individual communities is visible, but the bridges that are required as each of us individually bring together the strands of our trajectories in multiple communities may remain invisible as it is a highly individual thing. ‘Even though each element of the nexus may belong to a community, the nexus itself may not’ (Wenger, 1998, p. 161).

- See also: Compare Wenger’s idea of reconciliation with Rogoff’s discussion of adaptive expertise, Rogoff, B. (2003) ‘Thinking with the Tools and Institutions of Culture’.

Multimembership ‘forces an alignment of perspectives in the negotiation of an engaged activity’ (Wenger, 1998, p. 218). With that alignment you become a bridge between the communities, which increases learning as you engage with both and as you reconcile them within yourself.

- See also: Possible examples of multimembership being expressed in:

- The story of Daniel: Hall, K. (2008) ‘Leaving Middle Childhood and Moving into Teenhood: Small Stories Revealing Identity and Agency’.

- The story of Jake: Hicks, D. (2012) ‘Literacies and Masculinities in the Life of a Young Working-Class Boy’.

- The story of the Design and Technology class: Murphy, P. (2012) ‘Gender and Subject Cultures in Practice’.

Identity is belonging, which is defined globally but which we experience locally

The best example of this given in the chapter is that we may be affiliated with a political party (global), but our discussions about politics over lunch (local) may have more of an effect on our ideas.