Scientific literacy and cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT)

These notes are part of a series for the book. This paper looks at scientific literacy in terms of cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT).

Outline

- Background

- Scientific literacy

- Cultural-historical activity theory

- Rethinking scientific literacy

- Community water problems as curricular topic

- School science in the community

- Scientific education as everday praxis

Notes

Scientific literacy

This is often thought of as the transmission of knowledge about basic concepts, principles, and theories. This definition leaves out, or squeezes out, women and minorities who may understand science differently.

The authors propose:

- “Citizen science” which focuses on things the average person is interested in (such as public health issues, farming, etc.) and the ability to find those with specialized knowledge, since knowledge is distributed.

- Because there is a distribution of labor and so some people are more knowledgeable than others, we should think of scientific literacy as a collective activity.

- We should take a multi-disciplinary approach to solving scientific problems.

- Participating in scientific communities of practice (CoPs) can result in lifelong learning and interest.

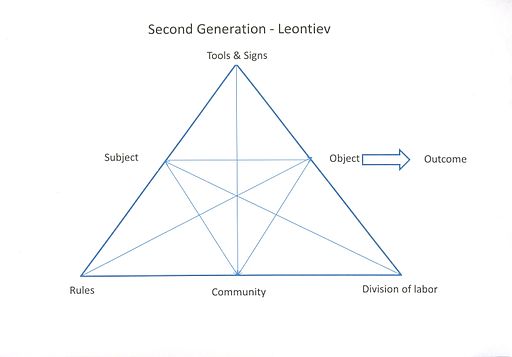

Cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT)

This is a theoretical framework. (Wikipedia has a good overview ).

Second Generation CHAT by Pronacampo9 is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Activity: A collective system (usually an institution) and a unit of analysis.

CHAT is based on six entities that define the domain:

- Subject (individuals or groups of people)

- Objects (can be artifacts or motivations)

- Tools

- Rules

- Community

- Division of labor

Activity system: Defined and motivated by the relationship between the subject and the object.

The relationship between the parts of the activity system (that is, between the subject and objects) is mediated by the other entities. For example, the subject (people) may use tools to better understand the object. Rules may govern their relationship with each other and the community. Labor may be divided among the subject (group of people) or across the subject and community.

The story of the Henderson Creek Project (HCP) and schools in Oceanside

HCP was an environmental group concerned with the local watershed. They worked for 2 years with the local school to co-teach a 2-4 month module to three 7th grade science classes. They involved the students in their work, which gave them legitimate peripheral participation and authentic work.

In particular, the girls and the First Nations students did not like doing the math part of data analysis. Instead, they wanted to do interviews, take photos, etc. Another child wanted to be the “historian” and capture the activities and learnings of others. These alternate activities were encouraged. The students guided their own inquiry and produced materials they felt were meaningful. See also: (personalized learning)

In the end, they gave a presentation of their materials (like a science fair) and answered questions from the adults who attended. “[I]t is in the interaction, in the questions and answers that scientific literacy emerges.” (p. 187) — this is similar to the findings proposed by Dysthe et al. about portfolio work.

In terms of CHAT, the specific entities depended on the subject and object, but in general were:

- Subject: The students, the members of HCP

- Object: Henderson Creek and the area’s watershed; students

- Tools: Measuring devices, recording devices

- Rules: Use of tools, math and averaging rules, quality rules

- Community: Oceanside; parents; scientists; teachers; students from other classes

- Division of labor: Researchers, knowledge producers

- Outcome: Correlations, classifications, reports, websites, processes, measurements

Application

The authors recommend that instead of building bridges to connect academic discourse with everyday life, they should involve students in the everyday life activities. That is, engage them in authentic activities within the CoPs now instead of preparing them for it later. Contrast this with Rogoff’s proposal for building bridges: